[ad_1]

After the appearance of the mainframe within the 1940s, it took lower than 20 years for computer systems to succeed in past the confines of navy R&D to turn out to be a broadly used platform for creative experimentation. Within the late 1950s, company analysis institutes like Bell Labs and the RAND Company started to look into the machine’s capacity to create artwork and music, and engineers initially orchestrated the making of those works. In 1963—two years earlier than something referred to as “pc artwork” appeared in galleries—the commerce journal Computer systems and Automation held its first “Laptop Artwork Contest.” The jury awarded first prize to Splatter Diagram, a computer-generated fractal graphic of a shattered digicam lens created by the US Military Ballistic Analysis Laboratories. Within the preliminary years of pc artwork, then, it was inconceivable to uncouple even essentially the most experimental makes use of of pc applied sciences from their affiliation with what the historian of science Peter Galison has referred to as “the Manichean sciences” of militarized command and management.¹

Computer systems had been first developed to execute the complicated calculations that had been more and more a part of fashionable warfare: ballistic trajectories, cryptography, speculative modeling to nearly check the atomic bomb. Creating and sustaining the then immense and unwieldy machines required sprawling conglomerates with each private and non-private funding—RAND and the US Military Ballistic Analysis Laboratories being two of the extra salient examples. Entanglements of companies, the navy, and universities made computer systems potential and had been instrumental in figuring out their future makes use of. It was not incidental that the “glitches” that occurred in ballistic laboratories got here to be referred to as “pc artwork,” nor that firms like RAND initiated creative packages. These organizations had incentives to foster an expansive analysis program. They acknowledged the likelihood that the progressive, unprecedented outcomes would, in some unforeseeable however immensely worthwhile means, be wrangled to make sure a aggressive edge in one of many many arenas the place computer systems had been starting to take maintain.

Importantly, computer systems continued to make their means into artwork and tradition not regardless of their entanglement with the military-corporate analysis complicated, however due to it. The artworks, exhibitions, actions, and texts that comprise the early historical past of generative artwork had been meant not solely to combine computer systems into artmaking, but in addition to reimagine the political company of artists and artworks alike. Generative artwork, in different phrases, was tied to a generative understanding of artwork’s political position.

Courtesy Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Artwork Assortment (Spalter Digital).

That is most obvious within the writing and work of two of essentially the most influential figures within the historical past of generative artwork: German cybernetician and thinker Max Bense, who sought to quantify aesthetic expertise and computerize the creation and analysis of artwork, and the German-born, UK-based artist and activist Gustav Metzger, whose notion of auto-destructive artwork was supposed to dismantle the parable that know-how was rational or impartial, and expose the destructiveness at its very core. Regardless of their variations, each envisioned artwork as a laboratory for imagining how computer systems might defy their militaristic origins and be structured in response to different logics—the eruptive spontaneity of the inventive act, for instance, or the mutually helpful, horizontal processes of communication and collaborative motion. They every imagined generative artwork as a way of catalyzing a extra engaged public group and a extra clear, participatory, and democratic world.

Of the 2, Bense was the much less probably candidate for artwork theorist or inspiration for activists. He studied philosophy, physics, arithmetic, and geology on the College of Bonn within the 1930s and, after the battle, joined the philosophy school on the College of Stüttgart. Bense started writing about aesthetics within the 1950s, with the concerted purpose of calculating and quantifying this seemingly elusive (or at the least, ineffable) topic. His conception of artwork and aesthetics drew on plenty of precedents, specifically mathematician George David Birkhoff’s 1933 notion of aesthetic measurement, which outlined aesthetics mathematically as a ratio between order and complexity. Additionally vital had been mathematician Claude Shannon’s data concept—which statistically defines data in relation to the quantity of noise a sign encounters because it traverses a channel—and Norbert Wiener’s cybernetics, the research of communication inside complicated techniques, each of which contributed to the founding of recent computer systems and, not unrelatedly, reconceived people as information-processing machines.

Courtesy Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Artwork Assortment (Spalter Digital).

Synthesizing these sources, Bense envisioned artwork as a communications community through which aesthetic data flowed between artist, paintings, and viewers. He outlined aesthetic data because the sudden ingredient inside this area: aesthetic alerts transmit data insofar as they’re unpredictable. His components expands on Birkhoff’s, calculating the connection between complexity and redundancy—between common and irregular rhythm, for instance, or uniform and jagged shapes or spacing of strains. Bense’s ratio additionally takes into consideration the connection between the variety of potential variations inside a selected medium or machine (tones in music, spectrum of colours, and so on.) and people actualized within the work. For Bense, a profitable paintings pushes the boundaries of communication and expands expertise, however doesn’t go as far as to exceed the viewer’s capacity to course of the work. This stability between creativity and conference, Bense claims, is artwork’s raison d’être. His understanding resonates with definitions of the avant-garde as breaking with custom, however right here, rupture could be routinely produced, statistically measured, and mathematically outlined.

Counterintuitively, given Bense’s fixation on “data,” none of this quantities to new information or that means in any widespread sense of the time period. In Bense’s view, aesthetic data measures the formal novelty of a piece. His concept wrests aesthetics from the contingency of subjective associations and the whimsy of style, making it a methodical investigation of the probabilities and limits of creativity inside a system. The subjectivity and ineffability often related to these sorts of experiences are eradicated, subsumed by mathematical formulation. Bense’s concept of generative artwork assumes not solely that aesthetic expertise could be measured however that it may also be rationally and predictably produced.

Courtesy Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Artwork Assortment (Spalter Digital).

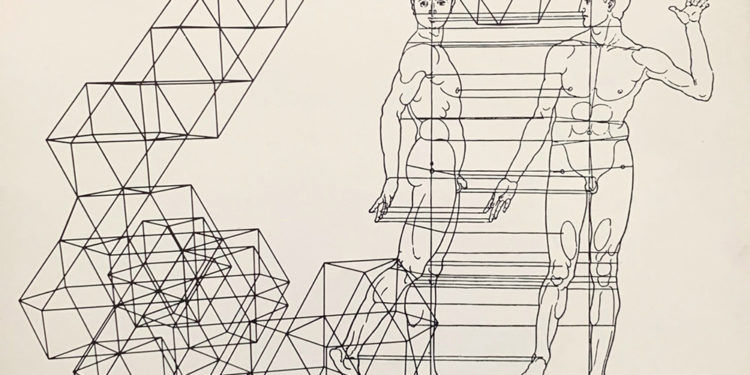

The end result of Bense’s concept was a brief 1965 essay referred to as “The Initiatives of Generative Aesthetics,” which introduced a set of schemas for evaluating aesthetic states alongside a set of formulation for exciting it by means of “a methodical mixture of planning and likelihood”—irregular or randomized parts mixed with ordered ones. Manufacturing took precedent over reception; it was actually a concept of generative artwork, somewhat than aesthetics. The textual content was written to accompany an exhibition of Georg Nees’s computer-generated graphics on the College of Stüttgart gallery, which Bense had based in 1958. Nees was an engineer who in 1964 started experimenting with what he referred to as “statistical graphics” at his company job, the place he had entry to computer systems and a programmable drawing machine, the Zuse Graphomat Z64. He used a easy algorithm to instruct the machine, for instance, to distribute eight dots inside a sq. and join them with a closed line. The outcomes had been easy geometric line drawings resembling Eight-corner (1964), a gridded association of small glyphs comprising jagged, crisscrossing strains. The work illustrated not solely the creativity of algorithms, but in addition the rational foundation for aesthetically balanced types, presumed to be lovely. Every thing about these works could possibly be related to some mathematical precept. As Bense put it, “the purpose of generative aesthetics is the synthetic manufacturing of chances, differing from the norm utilizing theorems and packages.”²

The political impetus of generative aesthetics may be simply misplaced on this sea of equations, formulation, and technical language, if not for Bense’s personal insistence on the urgency of this method. Bense argued that rationality is humanity’s first protection towards fascism. He was against Nationwide Socialism, and through the battle labored in Berlin as an engineer and physicist at a high-frequency engineering laboratory that made transmitters for the Navy. (Based on Bense’s spouse, Elisabeth Walther, the lab additionally secretly produced tools for Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, a covert resister to the Nazi regime.)³ Within the postwar interval, Bense turned a vocal critic of what he perceived because the persistence of legendary, irrational currents in German tradition. Fascism might need been over in Germany, however its epistemological seeds could possibly be discovered in every single place. Bense’s concept of generative aesthetics works to take away subjectivity from artwork and aesthetic judgment and imbue each with the transparency and readability of science—striving, in his phrases, to “remodel the metaphysical self-discipline right into a technological one.”four Underlying all of the technical language of data, complexity, redundancy, and indicators was an try to salvage that means in an more and more dispersed and confused data age, whereas on the similar time expressing an anti-totalitarian skepticism about whether or not such shared that means was potential or fascinating. Bense’s generative aesthetics—in addition to the experimental practices that it impressed in Nees and different German engineer-artists like Frieder Nake—was a sustained inquiry into the probabilities for a extra clear, participatory technique of collective communication.

Courtesy Generali Basis/Museum of Fashionable Artwork, Saltzburg. Photograph Werner Kaligofsky.

Whereas the aesthetic Principle Bense developed in Stüttgart harassed the coherence of the artwork-as-network, Metzger’s auto-destructive artwork sought to speed up and amplify the anti-systematic nature of the inventive act. Like Bense, Metzger got here to computer systems by means of a circuitous and interdisciplinary route. Metzger was born in Nuremberg, Germany, in 1926, however left in 1939 as a Jewish refugee through the Kindertransport to England. He labored as an apprentice cabinetmaker in a furnishings manufacturing unit in Leeds from 1941 to 1942, and lived for a short however influential interval in Trotskyist and anarchist commune in Bristol. After the battle, Metzger studied artwork at Borough Polytechnic in London with David Bomberg, whose work of the 1940s testified to the catastrophic influence of technological warfare that he witnessed through the Blitz. Following Bomberg, Metzger’s creative apply was built-in along with his activism, and centered on a priority with the devastation wrought by know-how; all through the 1960s, Metzger was an energetic participant within the antinuclear motion. However not like Bomberg, who expressed concepts about know-how by means of the medium of portray, Metzger—propelled by his political considerations—experimented with new media, integrating destruction as a productive ingredient within the creative course of.

Metzger’s first manifesto of auto-destructive artwork was written in 1959 and printed on a broadsheet to accompany the exhibition “Cardboards, chosen and organized by G. Metzger,” held at a coffeehouse run by his artist pal, Brian Robins, in central London. Discarded remnants of a TV-set carton had been displayed with none modification, highlighting the fabric particles produced by this thrilling new know-how—a seemingly democratizing innovation—as proof of the inherent wastefulness of shopper capitalism. “Auto-destructive artwork is primarily a type of public artwork for industrial societies,” Metzger’s manifesto started. Comprising solely eight sentences, the textual content asserts that auto-destructive artwork is an artwork of course of; it doesn’t matter what materials is used or who makes it (“The artist could collaborate with scientists, engineers”).5 What’s essential to auto-destructive artwork is that disintegration, ephemerality, and, most essential, destruction all determine centrally within the work.

In Metzger’s subsequent manifestos, the message is more and more political and the metaphor of destruction extra compounded. The second, written in 1960, is explicitly anti-capitalist and anti-war:

Auto-destructive artwork re-enacts the obsession with destruction, the pummeling to which people and much are subjected. Auto-destructive artwork demonstrates man’s energy to speed up disintegrative processes of nature and to organize them. Auto-destructive artwork mirrors the compulsive perfectionism of arms manufacture.6

The third manifesto (1961) ends much more assertively: “Auto-destructive artwork is an assault on capitalist values and the drive to nuclear annihilation.”7

Courtesy Generali Basis/Museum of Fashionable Artwork, Saltzburg. Photograph Werner Kaligofsky.

The second manifesto was meant to accompany Metzger’s Mannequin for an Auto-destructive Monument (1960), three metal towers that might step by step disintegrate over a interval of ten years. Since he was unable to safe funding, the monument was by no means constructed. As a substitute, he organized his first public lecture/demonstration, using a technique he would repeat a number of instances: stretching nylon over a sheet of glass and utilizing brushes and a twig gun to soak the material with hydrochloric acid, in order that the nylon disintegrated. Metzger wore a gasoline masks through the efficiency, which gave it a way of urgency and anticipated apocalypse.

Later incarnations included new media, and thus, levels of mediation. In a 1963 lecture on the Bartlett Faculty of Structure, London, the artist used a projector, masking slides with nylon and acid to show the method of disintegration on a display. Within the 1965 Chemical Revolution in Artwork, Metzger changed the nylon/acid mixture with heated liquid crystals—a tactic he would later use to create luminous stage backgrounds for bands resembling Cream and the Who.Eight Whether or not carried out or projected, Metzger’s works operate as apt illustrations of methods to render damaging processes inventive and humane. Constant along with his largely discursive output, Metzger organized the “Destruction in Artwork Symposium” in London in 1966, a two-day convention that drew a world array of artists, together with Yoko Ono and Vienna Actionist Hermann Nitsch, and evidenced the substantial overlaps amongst physique artwork, efficiency, and new media apply at the moment, particularly a shared concern with the intertwined histories of violence and speedy technological change.

Alongside these lectures, performances, and discussions, and more and more in his manifestos, Metzger built-in the pc as a privileged collaborator within the creation of auto-destructive artwork.9 From 1965 to 1969, he conceived and modeled varied variations of 5 Screens with Laptop, a computerized, degenerating public monument meant to occupy the courtyard of an house complicated.10 5 partitions, every thirty ft excessive, forty ft throughout, and two ft deep, can be spaced twenty-five ft aside. Every wall can be composed of 10,00zero items of metal, plastic, or glass, which might be randomly ejected over the course of ten years. The timing of those projectiles can be programmed by a pc, factoring in variables resembling climate and the revolution of the earth. Metzger imagined barrier manufactured from glass or compressed air might adequately preserve individuals out of the hazard zone as the weather crash to the bottom. These sporadic projectiles and the gradual disintegration of those public constructions would continuously remind residents that destruction and entropy in the end govern their materials world. As Metzger put it in 1965, “structure can be utilized to undermine values, to protest, subvert and destroy.”11

35mm slide projections, 22 minutes.

© Tate.

As this abstract could already recommend, there’s a profound ambiguity on the foundation of Metzger’s auto-destructive artwork. Is the work meant to reveal the damaging logic on the coronary heart of our technologically mediated world? Or does auto-destructive artwork render the unfavourable right into a optimistic, harnessing disintegration as a inventive precept? It appears nearly inconceivable for destruction to be each, however that is precisely what Metzger posits. The worst manifestations of destructiveness—battle, waste, environmental disaster, and the capitalist system behind them—all should be laid naked and eradicated. However destruction, on the metaphorical stage of the paintings or social critique, could be wielded to create a productive opening. This optimistic impact of destruction is obvious in 5 Screens. As Metzger defined in 1971, “Since there is no such thing as a viable energy construction or ruling ideology, the work can function a testing-ground for the forging of recent ideas of social actuality.”12 Right here, the disintegration of the work prompts a collective reimagining of prospects.

The social significance of 5 Screens due to this fact derives from its interrelation with the encompassing group, particularly within the presumed analogies between synthetic and precise life. Due to its altering nature, Metzger believed that 5 Screens would give individuals a touchstone for understanding, speaking, and relating their very own private growth. Individuals would bear in mind births and deaths by way of the place the sculpture was in its course of. They’d mark essential occasions by growing the variety of projectiles—like a completely built-in and adaptable fireworks show. Not volatility however somewhat variability is the work’s key precept: 5 Screens, as an adaptable, interactive system, would function a concretization of the collective but mutable dimension of the areas and occasions that the residents share.

Normally, discussions of Metzger’s work foreground his critique of computer systems, with the know-how’s inextricability from wartime destruction and militarism assumed to be the central message of his auto-destructive artwork. However taking a look at his writings and works through which computer systems had been most centrally featured brings forth one other dimension of his concept, one which comes nearer to Bense’s notion of generative artwork. Metzger’s values of spontaneity and randomness appear to distinction starkly with Bense’s prioritization of programming and transparency, however each are resolutely involved with communication. Every sees the computerized creation of artworks as a concretization of some sort of extra moral collective life.

For Bense, this manifests in a circuit of communication primarily based on universally affective alerts and indicators; for Metzger, in a shared social area that may join particular person and collective experiences, occasions, and temporalities. For each, the ethics of their envisioned techniques stems from their transparency, dynamism, and skill to be understood by everybody. Each Bense and Metzger produced elaborate theoretical treatises—be it manifestos or a number of philosophical volumes. Clear communication is central to what they thought computer systems might give us, and important to no matter future collective life they imagined such applied sciences would possibly help.

Bense and Metzger understood that know-how was neither impartial nor unilateral. On the similar time, they acknowledged that it has the capability to actively help and maintain sure sorts of life, motion, and existence. At a time when it as soon as once more appears inconceivable to parse the unfavourable from the optimistic results of computerization, and the inventive from the damaging penalties of the social networks that they help and deny, it’s instructive to look again on figures who imagined different futures. Following the generative politics of Bense and Metzger’s visions would imply probing the constitutive energy of know-how to ascertain collective experiences and dealing to create, otherwise.

Courtesy Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Artwork Assortment (Spalter Digital).

1 Peter Galison, “The Ontology of the Enemy: Norbert Wiener and the Cybernetic Imaginative and prescient,” Vital Inquiry, vol. 21, no. 1, Autumn, 1994, pp. 228–266.

2 Max Bense, “The Initiatives of Generative Aesthetics,” in Jasia Reichardt, ed., Cybernetics, Artwork, and Concepts, London, Studio Vista, 1971. Initially printed in Bense’s journal Rot 19, in 1965. For a extra detailed account of Bense and “the Stüttgart Faculty” in English, see Christoph Klütsch, “Data Aesthetics and the Stuttgart Faculty,” in Hannah Higgins and Douglas Kahn, eds., Mainframe Experimentalism: Early Computing and the Foundations of the Digital Arts, Berkeley, College of California Press, 2012, pp. 65–89.

three Elisabeth Walther, “Max Bense und die Kybernetik,” in 10 Jahre Laptop Artwork Faszination, ed. Gerhard Dotzler, Frankfurt, Dot Verlag, 1999, p. 360. The founder and director of the Berlin laboratory, Hans Hollmann, moved to the US after the battle to work for NASA. In 1949 he despatched Bense a replica of Wiener’s writing on cybernetics.

four Bense, quoted in Claus Pias, “Hollerith ‘Feathered Crystal’: Artwork, Science, and Computing within the Period of Cybernetics,” tran. by Peter Krapp, Gray Room 29, Winter 2008, p. 120.

5 Gustav Metzger, “Auto-Harmful Artwork,” (1959), in Kristine Stiles and Peter Selz, eds., Theories and Paperwork of Modern Artwork: A Sourcebook of Artists’ Writings, Berkeley, College of California Press, 1996, p. 401.

6 Gustav Metzger, “Manifesto Auto-Harmful Artwork,” (1960), in Stiles and Selz, eds., Theories and Paperwork of Modern Artwork, pp. 401–02.

7 Gustav Metzger, “Auto-Harmful Artwork, Machine Artwork, Auto-Artistic Artwork,” (1961), in Stiles and Selz, eds. Theories and Paperwork of Modern Artwork, pp. 402.

Eight Metzger had lectured at London’s Ealing Faculty of Artwork in 1962, probably inspiring partly the explosive stage antics of then scholar Pete Townshend, quickly to turn out to be well-known as lead guitarist of the Who, a band identified for ending their performances by destroying their devices.

9 The second manifesto specifies: “The quick goal is the creation, with assistance from computer systems, of artistic endeavors whose actions are programmed and embody ‘self-regulation.’” Gustav Metzger, “Manifesto Auto-Harmful Artwork,” 1960, in Stiles and Selz, Theories and Paperwork, p. 402.

10 Metzger writes that 5 Screens “needs to be sited as a central concourse between three very massive blocks of flats, housing greater than ten thousand individuals, ideally within the nation.” Gustav Metzger, untitled paper on theme quantity three for the “Computer systems and Visible Analysis” symposium, Zagreb, 1969, Bit Worldwide 7, 1971, p. 31.

11 Gustav Metzger, Auto-Harmful Artwork: Metzger at AA, London, Bedford Press, 2015, p. 22. This can be a transcript of a lecture given on the Architectural Affiliation in London, February 24, 1965. That is essential, as a result of the that means of the work requires a constant group, and thus couldn’t be sustained in both a public park, for instance, or a non-public house.

12 Gustav Metzger, “Sculpture with Energy” in Higgins and Kahn, eds., Mainframe Experimentalism, p. 217.

This text seems underneath the title “The Social Conscience of Generative Artwork” within the January 2020 difficulty, pp. 50–57.

[ad_2]

Source link